|

Fit is, if not everything,

the next thing to it. Such was the consensus of the haberdashers and trainers queried about proper attire and accessories

for the show ring. Whether theirs was custom riding apparel or stock suits, ensuring a proper fit led the list of essentials.

Neatness and cleanliness came

close behind.

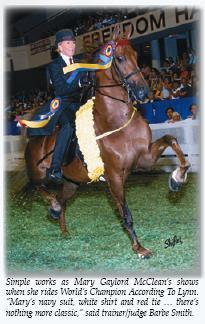

“You

can put a rider in a $3,000 suit, but if they play in the dirt before they show,” said Barbe Smith, a former equitation

star and today a trainer of top equitation and performance riders as well as being one of the judges for the 2008 World’s

Championship Horse Show. “A rider being dirty shows disrespect for what they are doing.”

She

addressed another question: that of accessories. “Judges are not looking for bling. They’re looking for horsemanship.

I like a limited amount of jewelry: small pearl or diamond studs for earrings and no big lapel pins.”

The

late Helen Crabtree and Lillian Shively helped set the styles in riding apparel, particularly where equitation riders are

concerned. Both helped Carl Meyers and later tailors bring riding clothes into the modern world. Whitey Kahn had just left

Meyers and established Le Cheval when Meyers joined the family company to run the riding department.

“Lillian

has a wonderful style and color sense,” Meyers said, explaining he specialized in dressing equitation riders in his

early days with the company. “She probably has the prettiest leg on her riders’ jods of any of the trainers. Jods

should have a very snug, snug type leg to the bottom of the calf, taper at the ankle down over the bell and then taper off.

“The

jod probably is the hardest piece to make,” Meyers continued, calling jodhpurs “a very intricate piece of art

work if you look at it that way. What Lil does is to pull tie-downs so tight there is not a wrinkle in that jod provided it’s

the right fit and is cut right.”

Marsha

Shepard has seen the saddle seat world from the perspective of an exhibitor, a trainer and now custom clothier. The de Arriaga

portion of her company name is the surname of her partner and prep school friend. De Arriaga’s father owns a boots and

bag company in South

America, one reason the friends initially specialized in leather goods. Shepard moved into riding apparel in the

late 1980s.

“Our fabric is not designed

to be riding clothes. We make things so tight they’re like a second skin, and then wonder why they split.”

Fortunately, the mount and dismount equitation test has been taken from the rule book. There were many reasons,

but one can’t help but wonder if one cause was related to riders splitting jods in the show ring.

“In

our division, we’re at the mercy of menswear fabrics. Some is very fine and sells for a great deal of money. No one

dreamed it would be used to ride on a sweaty horse and be dry-cleaned every week,” Shepard added.

No

matter how good a tailor may be, Shepard pointed out that fitting every body type definitely is a challenge. She compared

that to a personal experience of her own.

“I

had a great hairdresser and asked her to do many things. She told me, ‘My dear, this is a comb, not a magic wand.’

What I have is a tape measure, not a magic wand,” she quipped.

Fitting women, particularly those

with larger busts is a challenge for all the custom clothiers. Each addresses the question in a slightly different way.

“Most

women’s patterns are adapted from men’s patterns,” Shepard said. “If you make a suit large enough

to cover a rider’s butt, they look like a box on the saddle. The traditional cut saddle suit certainly is not something

one would choose for extremely busty, large woman. Unfortunately, the one-button coat just does not cover someone who is a

size 16 to 18 and up. It’s very difficult to get the coat to lay properly on them.”

One thing many riders overlook

when fitting a coat while not on the horse is wearing proper foundations. “There are some wonderful bras. They’re

important not only because they can minimize a little, but they offer protection for, rather than stretching the bust. A lot

of larger busted ladies would like slimmer if they had a coat that emphasized the waist and minimized the bust line,”

Shepard said.

As

did the others, Shepard has designed a pattern for women. As a rider and trainer, one of her many dislikes was ripples up

and down a rider’s arms. Part of her solution came from the conductor of the Boston Symphony.

"I happened to be at the symphony

watching the conductor. I wondered why the back of his jacket hadn’t changed when he directed with his arms up,”

she said, explaining a conductor’s basic arm position is similar to that of a rider. “I found the gentleman in

Boston

who did custom tuxedos for the symphony director. He was kind enough to share his secret with me.”

The

history of R.J. Becht and Sons of Ohio reflects that of the Meyers family. Frans M. Becht was a custom tailor commissioned

to make riding clothes (primarily hunt seat coats and breeches) for the U.S. Cavalry. Elise Becht Hauenstein is the fourth

generation of her family to pursue the profession.

“My

father took over the company in the 1920s,” she said, pointing out that Raymond J. Becht rode Saddlebred jumpers from

his farm in Indian Hill, near Cincinnati, Ohio. He helped move the

family custom clothing business in the direction of riding apparel rather than street clothes.

“We

are one of the few companies that do our own work,” Hauenstein said. “My brother, R.J., and sister, Barbara, measure.

I will personally cut every suit and pattern in the house. I put the pattern onto the cloth which then goes to our Cincinnati

shop. I like the control. It doesn’t mean that I don’t make mistakes; I can and have. I like having the control

of everything being right here, not dealing with another company, its rules, ways and employees.”

She spoke of some challenges in

fitting individuals. Getting a proper fit and line over a woman’s bust is near the top of the list.

“I make a pattern to fit

the individual,” she said. “If someone is large busted with a smaller waist, for the most part we can get that

down. Little people are very hard to deal with. I’ve worked with adults who are a size one or two and as wide as they

are tall. Their waist and hips fall together. I have to do a little more tweaking to fit them.”

Hauenstein has 25 people, all

specialists, who put together their riding apparel. Two do nothing but hang sleeves. One does all the hand work, another pockets

and zippers.

Fit certainly is important. “Most

equitation kids’ legs are extremely fitted through the legs and calf. Judges are looking at the rider. A child likes

the snug fit. For performance, a rider may not want the pants to be that tight. When you make a pair of jods, you need to

reach a point between fitted and comfortable. A rider can’t concentrate on what she [or he] is doing if she’s

worried about what’s coming apart.”

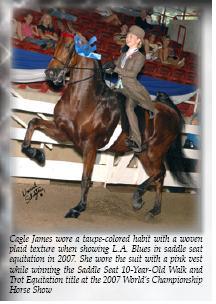

Lillian Shively has done much

to set the style and emphasize fit for equitation riders. “I felt like a lot of my riders, and especially the younger

ones, did not look good in blacks and browns. They had the rest of their lives to wear black. There will come a time when

they cannot wear anything else,” she said, explaining she put the first light-colored equitation riding suit in the

ring. “I went with more flattering, complementary colors that the children felt good in.”

“Lillian

wanted a look that complemented the girl more so than the horse,” Carl Meyers said. “We got very concerned with

a kid’s complexion, with the total look. Their suits blended with their horse, bringing the kids off the saddle a little

bit and showing their legs.”

So what about colors? USEF rules

are specific about those worn for equitation. “Informal: Conservative colors are required (i.e., herringbone, pin stripes

and other combinations of colors that appear to be solid). Solid colors include black, blue, grey, dark burgundy, dark green,

beige or brown jacket with matching jodhpurs; derby or soft hat. Formal: Even more conservative attire is required for evening

classes. Solid colors include dark grey, dark brown, dark blue or black tuxedo-type jacket with collars and lapels of the

same color, top hat, jodhpurs to match and gloves, or dark-colored riding habit, accessories and jodhpur

boots.”

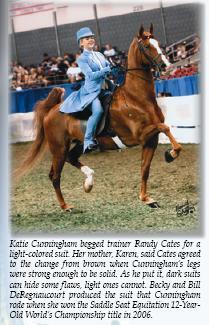

“The

USEF rules give a very basic guideline; few are following it,” said Becky DeRegnaucourt, who, with her husband, Bill,

owns DeRegnaucourt LTD. “Judges are pinning riders who are in violation of that. There are those that are very borderline.

One judge flat out disqualifies a rider when they’ve been pinned first the whole season.”

Unlike

other custom tailors, the DeRegnacourts have no store front, and spend most of the year on the road.

“I

think colors should be [appropriate] by age group,” she continued. “I don’t believe we want six, seven and

eight-year-olds in black and dark navy blue. And I don’t think what an eight-year-old wears is appropriate for a 14-year-old.

Riding apparel is so expensive. People try to be somewhat individual while abiding by the rules. It’s very emotional

for these kids to know they are doing the right thing.”

Other than showing in a formal

habit in evening three-gaited classes, there are no set rules for performance riders. Individual taste and what looks good

on the horse and rider are the sole limits.

“The

first thing a judge sees as you come through the gate is your coat,” Hauenstein added. “If you’re wearing

bright yellow and the judge doesn’t like the color, it might affect his judgment.” Shepard agrees that a coat

“should be tasteful and complement the horse, not necessarily the rider. A rider’s hair isn’t down and he

can’t see their skin tones.

“In the world of fashion

in general, you have to be very careful how you choose color. Contrasts chop up the body,” she said. “A size two

or four can wear anything. A larger person should wear colors suitable with colors of the horse. You try to draw attention

to the positive, not negative things. If a rider is heavy on top, whatever is big is going to look bigger if the coat contrasts

with pants. You want to blend them together with one solid color. A larger woman might wear a three-piece suit and add color

with a shirt and tie. It’s important to blend in with the horse if you want to draw attention away from the rider.

“I think the question of

colors for little children came up because if they’re on a black or bay horse, you can’t find them. Lighter colors

help them show up.”

DeRegnaucourt

spoke of linings, and the problems presented by such vivid contrasts as a navy suit with red lining. “That was a distraction,

bringing attention to the rider’s legs and knees. It was great for certain people, but not for everyone. You don’t

want to draw attention to unattractive areas of the body.”

Today,

many ‘day coats’ are silk or silk and wool blends. In selecting a color, Shepard says that more than personal

preference is to be considered.

“I like looking at the horse,

to assess the conformation of the rider and that rider on the horse she has chosen to ride. If I were putting a rider on a

fairly low-headed horse, I wouldn’t choose a bright yellow coat. That would show the horse’s headset to be lower

in the bridle than the competition. If a rider were tall from the seat up, I wouldn’t put a bright silk coat on her.

“We’re

cutting riders up so much today when we use a bold vest, bold shirt and tie. Judges [and fans] are looking a very short distance

from the rider’s shoulder to waist. A rider’s beautiful long, lean body disappears when you put her in a crazy,

bold vest, bold shirt and tie and collar accent. You lost the rider’s neck. Add a bun and hat and pretty soon little

Suzie is gone.”

Shepard

cautions that the length of a coat has a lot to do with proportion of horse and rider. As she works with both Saddlebred and

Morgan riders, she sees such challenges on a regular basis.

“A

short rider comes across with her coat at the middle or just below the knee when she is mounted with her foot in the stirrup.

If a rider is mounted on a short-backed horse [such as Morgans,] if the rider has too long a coat it looks like a serape on

the back of the saddle. Don’t follow trends or fads – really analyze the combination you are putting together.”

Shepard

concedes she is her worst critic. “Sometimes I lay awake at night fussing over something I can’t figure out. Sometimes

what looks great standing up looks totally different when a body is in the saddle. We have some ladies who are short-waisted

and want to look longwaisted on their horse. Doing that without ripples in the back of the jacket or opening up the hips enough

so the waist drops down is a challenge. We have to create an illusion.”

So

what separates the more popular custom tailors from one another? All use good grade menswear. All use custom measurements

– some provided by trainers or other professionals, some done at shows or in the shop. One may have a unique touch to

a pair of jods, coat or vest that often isn’t visible to the casual eye.

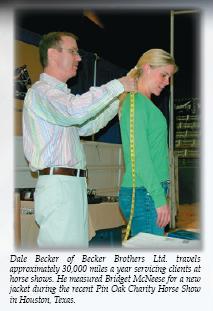

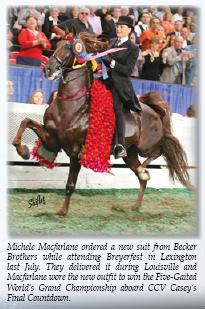

“Service,”

Dale Becker of Becker Brothers in Lexington, Ky., said, describing what

he thinks sets one apart from another. Becker worked 17 years for Carl Meyers before he and his brother, Michael, bought the

business, changing its name to Becker Brothers in January 2007.

“People have a choice when

buying a riding suit. Service is most important – that’s what sets us apart,” he said. “I travel about

45 weeks a year to different barns, conventions and horse shows.”

In March of this year, Becker traveled from Tampa, Fla., to Arizona,

to Houston, Texas to Raleigh,

N.C. At each show, he personally took clients’ measurements for new apparel,

marked alterations, discussed fabrics and accessories. Before the season’s end, he expects to attend 23 more such events.

“I

travel 30,000 to 35,000 miles a year,” he said. “I don’t know anyone else who travels as much as I do.”

In the span of Saddle Horse clothing

history, Carlos Chavez of Minneapolis, Minn., is a comparative newcomer. He expanded

from doing men’s and women’s custom clothing into equestrian wear 18 years ago.

“The way I’m different

is quality control. My show jods, vests and denim jods we make in store. Jackets are contracted out and we do the finishing

here,” he said, pointing out that being a smaller company gives him an advantage over some others. “I look at

every single piece that leaves my shop, no matter what it’s for. I press every garment and inspect every one that leaves

my store. If it’s something I don’t approve of, I have it redone until it meets my specs.”

Four

years ago, Chavez bought a Saddlebred and began riding. “I think customers realize that, since I am a rider, I understand

the function of the garment on both horse and rider. For the past 18 years, I have been perfecting the coat pattern. Looking

for a better fit, look, function and comfort is a never-ending process.”

Chavez’s custom denim jods

have met an industry need. The first pair he made for himself, and then his trainer, Todd Perkins, of Centerpoint, tried them.

“He

didn’t give them back. I had to make another pair for myself,” Chavez said with a smile. “They’re

98 percent cotton and two percent spandex so they will give. I designed them a little differently with a snap in the back

of the cuff and ultra suede in different parts of the jods.”

The new jods met the need for

practice jods that could be tossed in the washer and dryer and would stand the tests of time and wear. Later, trainers began

asking for black stretch denim jods to wear when they run in the ring, something he produces today.

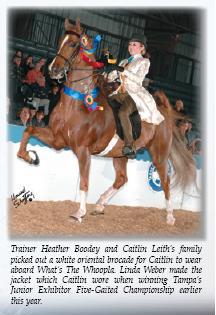

When Linda Weber of Hawkewood

Farm, near Tampa, Fla., takes to the road it’s often with horses

and her tack trailer. Not only does she bring samples of materials for custom riding clothing, she brings her sewing machine

as well.

“If

something needs a nip or tuck at a show, I do it,” she said.

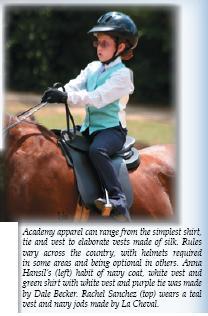

Weber

is known for her line of oriental silks, often used in vests although she has done a few jackets. She has made a number for

academy riders as well as for more experienced riders.

“Some

barns are not concerned about what their academy riders are wearing; some are very particular,” she said. “A rider

can spend $400 to $500 on an academy outfit, using regular stock jods fitted to her and a custom vest. Match a shirt, tie,

cufflinks and number pins, and it looks as if the entire outfit were custom made.”

Often

those just starting in academy or more advanced competition can’t afford or don’t want to make that big a commitment

to riding clothing. That’s when buying a good used riding suit makes sense.

“If

someone can’t afford a new suit, look for a good used suit even if it’s well used and has wear. If it’s

well made and well-fitted, she will do much better than with a poorly made suit. I will rework suits and make them fit well,”

she said, emphasizing fit as well as fabric. “Even a nice suit that fits poorly is detracting.”

Another

option is what Nancy Edwards of World Champion Horse Equipment calls ‘starter suits.’ World Champion and Hartmeyer

Saddlery each carry a good line of ‘stock’ habits. They cater to the academy rider as well as those seeking a

lesser-priced alternative to having a custom habit tailored.

“We’re

in the process of building a new line of riding clothes in an affordable price range,” Edwards said of the Shelbyville,

Tenn.-based company. We’ve added a new line of ladies and children’s vests with matching or coordinating ties.

We carry everything from starter suits for youth, ladies and men up to our new Champion Collection.”

They

also stock a full line of accessories, from Ariat and other boots, to gloves, derbies, homburgs and men’s dress hats.

Janie

Hartmeyer Ginter knows the Saddle Horse business from the standpoint of an owner, exhibitor, mother and fan. Based in Muncie,

Ind., the Hartmeyer’s staff has been dressing show riders for almost 40

years.

Their

Hartmeyer Elite line encompasses some of the best of custom tailored suits while offering substantial savings to clients.

They purchase their fabric from Dormeuil, a French company, or some wools from England.

“We

buy about $15,000 worth of fabric at a time and have navy blue Elite suits made,” Janie Ginter said. “We keep

all sizes of men’s and ladies’ pants, coats and vests in stock.”

Hartmeyer’s

Elite line can be purchased as separates, which answers one of the objections to purchasing a stock outfit.

“If

you outgrow, lose or tear a piece, a replacement is just a phone call away,” Ginter said, explaining one benefit of

using the same fabric and color on all suits. “That’s one reason Hartmeyer Elite and Black Premier Formals have

such good resale value. If the coat fits well and the buyer needs another size pants, they can get it.”

The

clothes themselves are but one – albeit the most important – part of equestrienne wear. Shirts, ties, gloves,

hats (derbies and top hats for women, homburgs and snap brim headgear for men,) collar bars, tie tacks, cuff links, number

pins, lapel pins… the list goes on.

Underpasses,

the strap that goes beneath a rider’s boots, are most important. The DeRegnaucourts manufacture their own.

“Ours

are extremely short, probably half the length of the typical underpass on the market,” Becky DeRegnaucourt said. “Ours

hold the pants down on the boot. At times, when you see a rider whose pants seem too short, it may be that their underpasses

are too long.”

Like

the riding habit itself, shirts should fit. Many of the custom-tailored shirts feature eyelet holes that are reinforced for

the collar bar. Custom-tailored ones are more expensive than one that might be picked up in a men’s or boys’ department.

Off-the-shelf shirts should be altered so the collar and sleeve-length fit properly.

Ties,

with knots proportionate to the person wearing them, can be a statement that accentuates a rider’s overall appearance.

An appropriate-sized tie pin is acceptable as is a lapel pin that doesn’t overpower the rider.

Gloves

are more than an accessory. Although the rule book doesn’t address color, traditionally brown or black gloves are worn

in the day time, with white reserved for formal attire. Hartmeyer has added a longer glove to its collection this season.

Made of tough, flexible, hairless Nigerian Goatskin, the glove is manufactured to their specifications in England.

It is an inch and a half longer than traditional ones with a Velcro tab on the inside to give a smooth line underneath a cuff,

which should replace taping of the gloves.

Accessories

lead to an entirely new discussion. Lapel pins and earrings can bring about heated discussions between riders, trainers and

parents.

“Earrings

need to be a good size in relation to the rider and other jewelry,” said L.A. Bass of Churchwell’s Jewelers. “We

have learned that, in equitation, earrings need to be more tailored, rather than swinging and moving. They need to be an appropriate

size to be seen in a photograph in a magazine – not so small spectators and the judge can’t see them.”

With

custom jewelers such as Churchwell’s and the Gorgeous Horse having booths at many major shows, parents and young people

are introduced to ‘what is possible.’

Bass

knows the challenges of pleasing youngsters, parents and trainers. “We are not equestrian people, but jewelers. There

are a lot of nuances and details that we don’t think about first. A piece being pretty and well-made is most important;

the right/appropriate size is not a jeweler’s bag. If we’re in doubt, we suggest they take a piece to one of the

haberdashers and get their opinion.”

Obviously,

a six-year-old will outgrow her early earrings. “When she grows out of that age group, the mother can bring it back

to Churchwell’s to add a suitable icon to make the total piece larger for her to continue to wear. If a child loses

an earring, we are happy to replace half a pair.”

While

people see Churchwells – particularly L.A. and Anderson Bass and their families – at shows

throughout the country, there is more to the company than their traveling displays. Established in 1905, their ‘bricks

and mortar’ headquarters is in Wilson, N.C., 50 miles

east of Raleigh. Their third-generation web site features

a full line of equestrian jewelry as well as the new nautical jewelry collection and fine pieces for any occasion. Horse World readers again voted the

firm the 2007 People’s Choice Jeweler of the Year.

Jason

Maze of The Gorgeous Horse is the third-generation of family jewelers serving the horse industry. “Horse shows are the

only way we have made our living,” he said, pointing out that Saddlebreds and Arabians are predominant for them.

Theirs

is still a family business. Jason and his grandfather design most of their pieces. Jason does the stone setting and finishing

while his younger brother, Chris, is responsible for casting.

“Tie

tacks and earrings are our predominant accessories,” Maze said, adding that some people order custom collar bars and

lapel pins. “We’ve switched to locking backs to minimize someone losing jewelry while riding.”

While

high-end, custom jewelry make up most of their line, Maze carries a number of inexpensive, sterling pieces with him to shows.

“We sell a lot of this to the kids. They appreciate being able to spend their own money, buying something for themselves,

a parent or grandparent.”

Candy

Walthers of A & H Enterprise brings a different perspective to the custom jewelry business. She was a horsewoman long

before she began her new career. As a member of the Mountjoy family, she grew up on the historic Lawrenceburg,

Ky., farm.

“I

baled hay, fed sheep, goats and cattle, milked cows and helped care for the beef and dairy herds – as well as over 400

head of horses,” she recalled.

She

trained and showed Saddlebreds for years before becoming involved with jewelry. That experience has helped her in designing

appropriate and ‘safe’ jewelry, particularly for riders. One difference is the back she puts on lapel pins and

tie tacks.

“I

recommend a pin large enough to be seen on a jacket, something that isn’t a speck but isn’t overly expensive.

It’s overkill for a young child,” she said. “Often the kids won’t get a pin-back on property. After

a ride, they hug their horse, a friend, trainer, parent –even a dog. The next thing you know, they don’t have

a lapel pin.

“I

make my pins with a bale in back. This allows you to fasten it with a safety pin. That doesn’t show, but helps prevent

a child losing it. They also can wear it as a pendant by adding a chain to the piece. I want something to be a multipurpose

piece a child can put on, love and enjoy in many ways, not come back and say, ‘Candy, I lost it.’”

This

season she also is emphasizing a ‘design your own earrings’ program. Unlike most other custom jewelers, Walthers

does not set up a booth at shows other than Lexington Junior League. Nor does she have a store front. Rather, she visits with

individuals, carrying samples, taking orders and making deliveries at a place convenient to her clients.

In the show horse world, being

a fashion plate doesn’t earn you blue ribbons. But being correctly attired, correctly accessorized and – most

of all – correctly turned out could make the difference when all else is equal.

|